CO-CREATION

IN PRACTICE

TOPIC 4

Teaching students to co-create

In order to function as a professional in a VUCA world, students must be capable of developing new behaviours that provide a valuable response to the challenges of tomorrow. The rapid evolutions in the professional field and in society will increasingly be facing our graduates with complex issues that are difficult to predict. Consequently, it is important for us to focus on advancing their capacities for solution-oriented approaches and for harnessing collective intelligence to address such issues.

The fact that co-creation and the capability to work in an inter-disciplinary manner are key competencies for the future is also demonstrated by the ESF focus studies into future competency demands in various sectors in Flanders (Van Hove & Desseyn, 2017): “The capacity to acquire personal, specialist knowledge will only be appreciated if the individual has the concurrent capacity to exchange such knowledge. Solutions are found in co-creation.” A more theoretical substantiation of the skills that the professional field expects of students can be found in this article: Professional expertise, integrative thinking, wisdom, and phronesis (Tynjälä, Heikkinen, & Kallio, 2020).

The attention for learning to co-create in order to be able to innovate and resolve complex issues is also reflected in the PXL University of Applied Sciences and Arts Authentic Education model and in the Odisee University of Applied Sciences views on co-creation:

Both views point out the importance of authentic contexts as a source of opportunities to learn to co-create. However, affording students the opportunity to work in an authentic context will not automatically induce them to (learn to) co-create.

Some important points of attention to encourage students to co-create:

Be alert to opportunities for co-creation that arise in the professional field.

Co-creation is based on an explicit urgency that is perceived by all the parties involved. Show your professional field partners that you and your students are open to addressing any challenges that they are faced with, show that you are interested, and take the initiative to ask for more information.

READ MORE

Be aware of competencies and attitudes that are important for co-creation and identify the skills that you want your students to develop.

Examples of competencies are: integrating ideas; entrepreneurship; system thinking; creative thinking; interprofessional/international collaboration. Set down pertinent learning outcomes in concert with the professional field and/or outline the attitudes that you want to encourage. Your efforts will bear even more fruit if you leave some room for variation, and if the teacher, the professional field, and the students can collectively consider which competencies will be developed.

READ MORE

Build up complexity step by step.

Co-creation is an intensive and challenging process. Dropping students unprepared into a situation that requires them to co-create a solution to a complex issue together with a professional field partner will result in frustration rather than in learning gains. Sufficient attention for a gradual approach is, therefore, essential.

READ MORE

Be congruent and request the same from the professional field partners.

Several cases have demonstrated that co-creation requires a different mindset on the part of teachers: if you wish to teach students to co-create, you must also be prepared yourself to enter into a co-creative process of exploration, in which you act as a fellow participant rather than as an expert. It is important in this respect to clearly explain the steps you are taking in the co-creation process, in order for the students to understand the reasons why.

Embarking on a co-creative process of exploration with students may also require a mind switch on the part of the professional field partners. In many cases, they will need to adopt a more vulnerable attitude than they would in standard forms of collaboration. It is advisable to check with the professional field partners in advance whether they appreciate what co-creation involves and whether they need support in learning how to co-create.

READ MORE

Adopt appropriate forms of evaluation.

An evaluation with a strong emphasis on scores does not chime with co-creation, because it can curb creativity. Furthermore, a range of parallel forms of evaluation is needed to gain a proper picture of a student’s participation in a co-creation process, which is influenced by many factors.

For that reason, several cases feature a combination of different forms of evaluation, focusing on formative and summative evaluation: self-reflection and self-assessment; coaching meetings that encourage reflection by students; forms of evaluation involving intersubjectivity, such as peer evaluations and presentations before a jury. In many cases, the professional field is also involved in the evaluation. Tanja Vesala-Varttala recommends experimentation with learning journals and portfolios.

READ MORE

Find solutions to practical thresholds.

In several cases, thresholds tend to be situated at the practical level. The participants have suggested several ways to deal with such thresholds.

SEVERAL WAYS TO DEAL WITH SUCH THRESHOLDS

Hogeschool PXL

Community-driven education within the PXL Authentic Teaching Model

PXL University College has opted for an educational concept revolving around authenticity, innovation, and co-creation. In order to map out and further develop the Authentic Teaching approach within its programmes, the university college has developed the PXL Authentic Teaching Model. The community-driven educational model within the Information Technology cluster of programmes is a pre-eminent example of how the PXL Authentic Teaching Model is being substantiated. Within community-driven education, the daily practices of the business community and the research centres are integrated into the programme. The collective creation of education for and by the community of junior co-workers (students), co-workers, companies, and researchers is the linchpin within the operation of the cluster of programmes.

PXL University College has opted for an educational concept revolving around authenticity, innovation, and co-creation. To support the design process, it has developed its own PXL model in which several elements play a distinct role: authentic context, authentic learning tasks, professional processes, reflection, and articulation of the thought process. This means that every component of the programme must feature a certain degree of authenticity, taking account of the above elements.

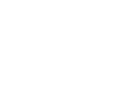

Figure 1: PXL Authentic Teaching Model

The model comprises five core elements:

- The continuous coordination of conceptualisation and contextualisation (horizontal axis);

- On the one hand, the university college as a place of learning and on the other, the professional field as a place of learning and working (dark grey range vs green range);

- Critical reflection throughout all the authentic teaching and learning activities (blue line);

- Five clusters of authentic teaching and learning activities (clusters A, B, C, D, and E):

- Developing discipline-based building blocks;

- Exploring the professional field;

- Project-based working;

- Participating in actual practice;

- Practice-oriented research;

- Clusters C, D, and E account for at least one-third of the activities.

The community-driven educational model within the Information Technology cluster of programmes is a pre-eminent example of how the PXL Authentic Teaching Model is being substantiated. This model focuses on integrating the daily practices of the business community and the research centres. The collective creation of education for and by the community of junior co-workers (students), co-workers, companies, and researchers is the linchpin within the operation of the cluster of programmes.

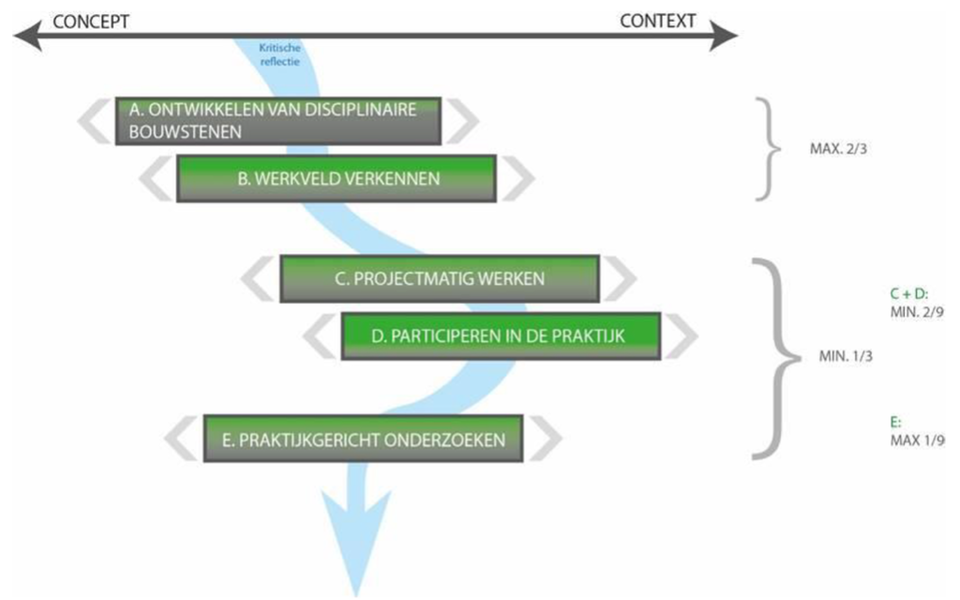

The Applied Computer Science professional bachelor’s programme and the System and Network Management first degree programme of the Information Technology cluster have used the model to authenticate their curricula. Figure 2 provides insight into the division of authentic learning activities across the various components. The model affords the programmes the opportunity to render authentic teaching quantifiable, comparable, and open to discussion.

Figure 2: Overview of Authentic Teaching clusters implemented in the Information Technology cluster of programmes

Within the Applied Computer Science professional bachelor’s programme, the model is implemented via programme components (clusters A and B) and via authentic projects (clusters C, D, and E). Cluster A equips the students with specific building blocks (knowledge elements and basic skills) of the Information Technology discipline. Theory is given meaning by establishing links with reality through, e.g., Pluralsight courses, guest lecturers, and authentic assignments that tie in with the students’ social environment (developing MasterMind games, setting up a databank for a cinema et cetera). In cluster B, the students explore the professional field. In seminars, workshops, and innovation routes they observe IT professionals and/or workplace processes. They sample new/modern technologies (chatbots, clean code, test automation, social engineering et cetera) that are subsequently explored, analysed, and ultimately linked to theoretical concepts. Furthermore, with effect from the 2020-2021 academic year, the programme has embarked on designing and teaching a full programme component in collaboration with the professional field. Taking the attainment targets as their point of departure, business professionals develop authentic curriculum content of the eBusiness programme component in collaboration with lecturers and equip students with the essential building blocks in a co-teaching process. In the lessons, they continuously establish links with the actual professional practice.

The third-year IT Project programme component is situated within the clusters C, D, and E; it is a pre-eminent example of authentic teaching. Within the IT Project, junior co-workers collaborate in multi-disciplinary teams (cluster C) on a project basis, working on an authentic assignment for a client/principal in a realistic professional context (cluster D). The result is a final product/prototype providing an innovative solution to a complex, actual practical problem (cluster E). For example, students have developed an omni channel shop prototype, in co-creation with the Elision company, aimed at helping customers find the product they are looking for in a shop while reducing the boundary between their physical and digital experience:

PXL iSpace is creating a realistic professional context at Corda Campus, the IT site of the Dutch province of Limburg, the Euregio Dutch-German collaborative network, and the Belgian community of Flanders. iSpace spans more than 1000 m² and features such facilities as an open project hall, a classroom, and innovation labs. It offers students a place to experiment and collaborate in an authentic framework, 7/7 and 24/24. Furthermore, iSpace is being enhanced with additional project halls embedded within companies based at Corda Campus.

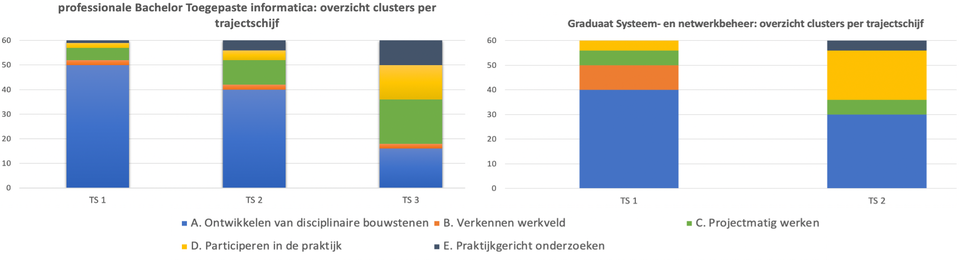

Within the System and Network Management first degree programme, the Authentic Teaching Model is being implemented via flanking programme components (clusters A and B) and work-based learning (clusters B, C, D, and E). It goes without saying that the programme has also embraced community-driven education. The learning process in work-based learning features a four-phase structure, as reflected in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Structure of work-based learning, System and Network Management first degree programme

In the Work-based Learning 1 phase, students are offered learning activities that enable them to get to know themselves and become acquainted with the professional field (cluster B, exploring the professional field). The emphasis is on becoming acquainted with the profession of system and network manager and on exploring technological evolutions within the domain. During guest lectures and company visits, hands-on experts explain their jobs and introduce students to present-day technologies. In addition, several workshops are organised to have students gain insight into their personal and professional identity and talents. In the Work-based Learning 2 phase, work-based learning is simulated via an authentic project (cluster C, project-based working). The project brief is formulated in consultation with the professional field. The professional field partners regularly provide interim feedback and assess the final product in collaboration with the learning coaches. The realistic professional context is once more created by iSpace at Corda Campus. The simulation projects ensure that students are sufficiently prepared before transferring to actual work situations in the Work-based Learning 3 and 4 phases (cluster D, participation in actual practice).

Added value

Students

Throughout the curriculum:

- Students are learning at and across the boundaries of school context and workplace. This expands their learning potential;

- Students are encouraged to adopt a project-based approach to finding solutions to practical problems;

- Students are practicing integrated professional skills, professional expertise, and professional mindsets in a realistic professional context;

- Students are learning to devise, field-test, and implement new methodologies and products that will result in the desired innovations;

Teaching staff

- Preserve a strong link with the professional practice;

The programme

- An up-to-date curriculum that ties in with the evolutions in the professional practice;

The professional field

- Influence on the study programme and the formation of excellent professionals;

- Graduates ready to start work immediately upon graduation;

- Opportunity to present themselves more distinctly to students (war for talent).

Challenges & opportunities

- Continued investment in the collective interests of co-creation;

- Coordinating and continuing to focus on the collective goal;

- Transparency in the collaboration in terms of expectations and responsibilities;

- Continued commitment to attracting good partners;

- Expanding collaboration with organisations/companies that are not active in the IT domain.

Contact

Professional Bachelor of Applied Computer Science

First Degree in System and Network Management

Corda Campus, Kempische Steenweg 293, Hasselt (Belgium)

PXL University College, Elfde-liniestraat 24, Hasselt (Belgium)

Tristan Fransen, Tristan.Fransen@pxl.be

Tine Aelter, Tine.Aelter@pxl.be

INSPIRATION

CASES

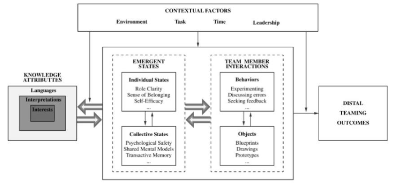

Model Edmonson en Harvey

Edmonson en Harvey (2018) bestudeerden grensoverschrijdende teams voor innovatie. Ze presenteren een model met een aantal factoren waarmee je rekening moet houden bij het werken in multidisciplinaire teams die gericht zijn op innovatie (Edmondson & Harvey, 2017).

#fab4+1 Odisee

Challenge Week Thomas More

Design for Impact LUCA School of Arts

Skill Tree-method LUCA School of Arts

International Summer School Sustainable Management Odisee

Circle Sector LUCA School of Arts

PAUW Erasmus Brussels University of Applied Sciences and Arts

Odisee University of Applied Sciences

Growth Path towards Co-creation

How does Odisee interpret co-creation?

- Co-creation is conducted by educational professionals, students, researchers, and actors from the professional field and/or from society.

- Co-creation is aimed at finding solutions to complex issues that the individual actors cannot manage to resolve on their own (no co-creation for the sake of co-creation).

- All the actors involved have an impact on the process and on its results; they contribute to the process; and they enhance one another based on their own expertise, experience, and talents (equality, mutuality).

- Co-creation serves the pursuit of a collective ambition and a collective result; the goal is to produce win-win situations.

- Extensive attention is focused on the quality of the process and of the relationships. This is a prerequisite for combining a range of perspectives and forms of expertise into collective intelligence in the pursuit of a new, valuable solution.

- In addition to the development of something new (product, service, policy, …), a co-creation process also results in the participants having learned (new knowledge/skills).

Co-creation is not a self-evident process. Various success factors determine whether or not the co-creation will be successful. An important factor is the point of departure for a co-creation process, i.e., an explicit urgency that is perceived by all the partners. Other pertinent factors include shared goals, trust, courage, and decisiveness (Ehlen, van der Klink, & Boshuizen, Co-Creatie-Wiel: instrument voor succesvolle innovatieprojecten, 2015)

Our ambition: a growth path towards co-creation

Our view on learning (learners must also be capable of developing new behaviours to address tomorrow’s new challenges; co-creation provides leverage in this respect) is contained in our Odisee 2027 vision document and in the Institution-wide Framework for Curriculum Compilation, for example, via such Odisee-wide learning results as co-creation, inter-professional collaboration, entrepreneurship, et cetera and via the principle of the learner taking responsibility. This view is most explicitly reflected in the fourth design principle: “actively learning in authentic and co-creative contexts”. The associated red line stating that all programmes are to incorporate into their curricula a growth path towards co-creation as outlined above chimes with this proposition. No more than learning how to swim on dry land can one fully learn to resolve complex professional issues on one’s own, outside an authentic work context.

Yet we cannot make absolute such authentic and co-creative contexts as educational concepts. Towards the end of their degree track, students must indeed be capable of addressing such complex challenges in a co-creative manner; however, Odisee does not maintain that its education can be interpreted as facing students with a succession of complex challenges in a variety of partnerships. Someone who expects insufficiently prepared students to address complex professional issues in the professional field is not educating them but setting them up for frustration. We prefer to take the safe road of step-by-step progression.

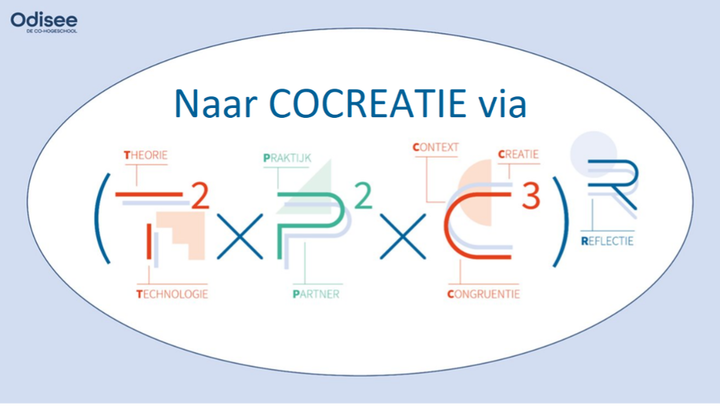

That is why it is important to have co-creation embedded in a more comprehensive view on proper education. The formula below links the concept of co-creation to the encompassing wider educational process.

Every student and future professional needs a Theoretical knowledge basis. However, this will be limited in terms of both breadth and depth, because no-one is capable of knowing everything about his field of expertise nor of following every relevant innovation. It is important for students to learn how to cope with such limitations while still at school. They need to be able to find missing information and to engage in interdisciplinary collaboration with other parties commanding complementary knowledge and skills.

A 21st-century professional is only worthy of this title when capable of applying the appropriate Technology in his professional practice. This will enhance the quality and the efficiency of said practice.

Universities of applied sciences are Practice-oriented in terms of their teaching, their permanent education, and their research. However, this practice is in a continuous state of flux. Here, too, students must seek a balance between delving into one particular section and appreciating what is happening in other sections of the practice.

All this can only be achieved in close collaboration with Partners who are willing to translate their know-how into state-of-the-art practice. Such partners are convinced of the necessity and added value of co-creation, with each participant contributing on the basis of his own expertise, experience, and talent.

Students must learn to deal with different Contexts, as the amalgamation of theory, technology, and practice cannot be taken for granted. Students must, therefore, proactively enter into relationships, engage in open communication with respect for each party’s individuality, and be allowed room to make mistakes.

Creation means: contributing to something new, something that is challenging and relevant to both the professional field partner and the programme’s students, lecturers, and researchers. This extends beyond applying knowledge and skills in the work placement practice.

The university of applied sciences aims to provide congruent education, to set a good example, to clarify the choices that it makes based on its views to students and to partners, and to substantiate such choices by reference to sources.

Reflection, finally, both individually and in a group, enables learning across specific theories, technologies, practices, partners, contexts, and creations. This is the only way for students to become sustainable, flexible, inquisitive, and enterprising professionals.

A growth path towards co-creation logically entails that the values of each of the factors in the process will continue to change. For example, in the first stage of the programme, comparatively more attention will perhaps be focused on theory rather than on creation. However, in the final stage of the programme, a student engaged in co-creation with a partner from the professional field and with a researcher from the programme will still be pursuing specialist knowledge to be applied in new, appropriate ways. The second important evolution in the process involves the increasing interaction, throughout the programme, between the factors identified in our definition. For example, a student will reflect on responses from various partners to a creative solution that he is proposing with respect to a shared shop floor issue. Students learn to recognise the interconnectivity between all these factors; learning to deal proactively with such factors in a complex reality undoubtedly requires an analogous growth process among teachers as well as considerable mutual trust.

Odisee University of Applied Sciences

Growth Path towards Co-creation

How does Odisee interpret co-creation?

- Co-creation is conducted by educational professionals, students, researchers, and actors from the professional field and/or from society.

- Co-creation is aimed at finding solutions to complex issues that the individual actors cannot manage to resolve on their own (no co-creation for the sake of co-creation).

- All the actors involved have an impact on the process and on its results; they contribute to the process; and they enhance one another based on their own expertise, experience, and talents (equality, mutuality).

- Co-creation serves the pursuit of a collective ambition and a collective result; the goal is to produce win-win situations.

- Extensive attention is focused on the quality of the process and of the relationships. This is a prerequisite for combining a range of perspectives and forms of expertise into collective intelligence in the pursuit of a new, valuable solution.

- In addition to the development of something new (product, service, policy, …), a co-creation process also results in the participants having learned (new knowledge/skills).

Co-creation is not a self-evident process. Various success factors determine whether or not the co-creation will be successful. An important factor is the point of departure for a co-creation process, i.e., an explicit urgency that is perceived by all the partners. Other pertinent factors include shared goals, trust, courage, and decisiveness (Ehlen, van der Klink, & Boshuizen, Co-Creatie-Wiel: instrument voor succesvolle innovatieprojecten, 2015)

Our ambition: a growth path towards co-creation

Our view on learning (learners must also be capable of developing new behaviours to address tomorrow’s new challenges; co-creation provides leverage in this respect) is contained in our Odisee 2027 vision document and in the Institution-wide Framework for Curriculum Compilation, for example, via such Odisee-wide learning results as co-creation, inter-professional collaboration, entrepreneurship, et cetera and via the principle of the learner taking responsibility. This view is most explicitly reflected in the fourth design principle: “actively learning in authentic and co-creative contexts”. The associated red line stating that all programmes are to incorporate into their curricula a growth path towards co-creation as outlined above chimes with this proposition. No more than learning how to swim on dry land can one fully learn to resolve complex professional issues on one’s own, outside an authentic work context.

Yet we cannot make absolute such authentic and co-creative contexts as educational concepts. Towards the end of their degree track, students must indeed be capable of addressing such complex challenges in a co-creative manner; however, Odisee does not maintain that its education can be interpreted as facing students with a succession of complex challenges in a variety of partnerships. Someone who expects insufficiently prepared students to address complex professional issues in the professional field is not educating them but setting them up for frustration. We prefer to take the safe road of step-by-step progression.

That is why it is important to have co-creation embedded in a more comprehensive view on proper education. The formula below links the concept of co-creation to the encompassing wider educational process.

Every student and future professional needs a Theoretical knowledge basis. However, this will be limited in terms of both breadth and depth, because no-one is capable of knowing everything about his field of expertise nor of following every relevant innovation. It is important for students to learn how to cope with such limitations while still at school. They need to be able to find missing information and to engage in interdisciplinary collaboration with other parties commanding complementary knowledge and skills.

A 21st-century professional is only worthy of this title when capable of applying the appropriate Technology in his professional practice. This will enhance the quality and the efficiency of said practice.

Universities of applied sciences are Practice-oriented in terms of their teaching, their permanent education, and their research. However, this practice is in a continuous state of flux. Here, too, students must seek a balance between delving into one particular section and appreciating what is happening in other sections of the practice.

All this can only be achieved in close collaboration with Partners who are willing to translate their know-how into state-of-the-art practice. Such partners are convinced of the necessity and added value of co-creation, with each participant contributing on the basis of his own expertise, experience, and talent.

Students must learn to deal with different Contexts, as the amalgamation of theory, technology, and practice cannot be taken for granted. Students must, therefore, proactively enter into relationships, engage in open communication with respect for each party’s individuality, and be allowed room to make mistakes.

Creation means: contributing to something new, something that is challenging and relevant to both the professional field partner and the programme’s students, lecturers, and researchers. This extends beyond applying knowledge and skills in the work placement practice.

The university of applied sciences aims to provide congruent education, to set a good example, to clarify the choices that it makes based on its views to students and to partners, and to substantiate such choices by reference to sources.

Reflection, finally, both individually and in a group, enables learning across specific theories, technologies, practices, partners, contexts, and creations. This is the only way for students to become sustainable, flexible, inquisitive, and enterprising professionals.

A growth path towards co-creation logically entails that the values of each of the factors in the process will continue to change. For example, in the first stage of the programme, comparatively more attention will perhaps be focused on theory rather than on creation. However, in the final stage of the programme, a student engaged in co-creation with a partner from the professional field and with a researcher from the programme will still be pursuing specialist knowledge to be applied in new, appropriate ways. The second important evolution in the process involves the increasing interaction, throughout the programme, between the factors identified in our definition. For example, a student will reflect on responses from various partners to a creative solution that he is proposing with respect to a shared shop floor issue. Students learn to recognise the interconnectivity between all these factors; learning to deal proactively with such factors in a complex reality undoubtedly requires an analogous growth process among teachers as well as considerable mutual trust.